Recently, Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim commented that Malaysia’s national debt has now reached RM1.5 trillion. This needs to be addressed urgently. It translates to more than 80% of the nation’s annual economic output or gross domestic product (GDP).

The PM alluded that Malaysia’s RM1.5 trillion debt comprises two parts, with RM1.2 trillion comprising the country’s total debts itself while the balance is related to off-balance sheet liabilities.

Based on the Fiscal Outlook and Federal Government Revenue Estimates 2023 tabled last October, these liabilities include committed guarantees, which stood at almost RM200bil. Other liabilities which are mostly lease payments for private-public partnership, pubic finance incentives and PBLT Sdn Bhd totalled some RM150bil. The remaining principal payments for 1MDB-related debts stood at about RM26bil.

As long as we continue to spend more than what we earn, we will remain in deficit and the nation would have no choice but to borrow and generations beyond us have to meet the obligations.

Under the Federal Constitution, the government is only allowed to borrow for development purposes and not for operating needs. Over the years, as we continued to spend for development expenditure, our debt level has been heading north. Revenue-generating ability has been restricted by a narrow tax base and an over-reliance on Petroliam Nasional Bhd dividends.

Under the Treasury Bills (Local) Act, 1946, the Malaysian Treasury Bills was initially capped at just RM20mil and the ceiling was revised in 1992 to RM10bil. Under the Loan (Local) Act, 1959, which had a cap of RM300mil before, it was revised to RM120bil in the year 2000. The nominal value capped ceiling was kept until March 2003 and thereafter Malaysia introduced a new cap in the form of a percentage of GDP at 40%. This allowed the government to continue to borrow in line with the growth of the economy.

Another two legislation that defines government’s borrowing is the Government Funding Act, 1983, which allowed the government to introduce syariah-based government securities while the External Loans Act, 1963, which allowed the government to seek foreign loans. Both of these acts were revised in 2006 and 2009, which enabled the government to increase the ceiling from RM1bil and RM300mil to RM30bil and RM35bil, respectively.

As Malaysia has been running budget deficits since 1998, the 40% debt-to-GDP ratio was also revised higher to 45% in June 2008 and a year later to 55% due to the Asian Financial Crisis. The debt ceiling was raised to 60% in November 2021 and to 65% now.

Based on the end-September 2022 update, Malaysia’s current statutory debt to GDP stands at 60% of GDP while the federal government debt to GDP was at 62.8%. The base assumption is that the nominal GDP will end the year at RM1,712.3bil (first nine months was at RM1,320.9bil) and there would not be further borrowings in the fourth quarter of 2022.

The Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) and the planned Medium-Term Revenue Strategy (MTRS), which the government is expected to table in 2023, are seen as key instruments for reforms.

A debt ceiling will put in place a rigid upper ceiling in terms of how much debt we can assume, be it RM1.2 trillion in statutory debt ceiling or any other figure, which will restrict any future borrowings unless approved by Parliament.

As we have seen in the case of the United States, the world’s largest economy has an absolute debt ceiling and it has also become meaningless as the Congress has no choice but to keep raising the debt ceiling level every time it is breached. Failure to do so will result in a government shutdown as it will be unable to pay its dues, especially salaries to civil servants and other obligations.

Another option is to have a definite debt-to-GDP ratio which will allow the government of the day to continue to borrow in the future as the denominator, which is the GDP, is expected to continue to expand.

Even assuming a 6% nominal GDP growth, which translates to about RM103bil GDP growth in absolute amount, Malaysia can afford to borrow at least RM66bil every year without breaching a debt-to-GDP ceiling of 65%.

The ability to borrow will increase in proportionate to the growth in GDP but capped at 65% of nominal GDP growth.

Both the absolute debt ceiling and the debt-to-GDP can be subject to abuse by a government of the day as it can always request for the ceiling or ratio to be raised. To instill discipline in the government, we must introduce a law that will restrict any government from raising this ceiling as it is detrimental not only to all Malaysians but adds further burden to future generations.

Malaysia should choose a hybrid model. For example, Malaysia can choose to have an absolute debt ceiling but subject to it not exceeding 65% of nominal GDP. If Malaysia intends to achieve a balanced budget within the next five years, the likely debt ceiling, based on the assumption that we would not spend more than 65% of the absolute nominal GDP growth, and assuming the nominal GDP expands by 6% per annum, perhaps a RM1.6 trillion federal government debt ceiling should be introduced.

Thereafter, Malaysia may work towards achieving a balanced budget by 2028, based on nominal GDP of RM2.46 trillion in five years. As for off-balance sheet liabilities, those will remain for now.

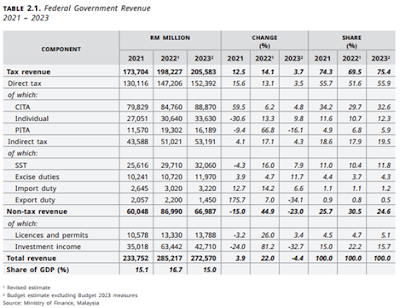

The MTRS plan should redefine how taxes are imposed on individuals and businesses. Malaysia is simply not collecting enough tax revenue at just over 11.3% of GDP for 2023 based on the original Budget 2023 that was presented in October 2022.

A new plan to raise taxes to enable Malaysia to achieve a balanced budget by 2028 needs to be presented. New taxes on forex transactions, wider coverage of windfall tax, higher individual tax rates at the top end and a wider SST may be necessary. It is still not right to introduce GST – when we are not a developed nation nor when our Gini coefficient is stuck at 0.4.

By 2028, tax revenue to GDP must reach at least 20%, which will then translate to approximately RM492bil in revenue.

A five-year plan to achieve a balanced budget is not impossible but what is more important is for the government to table a comprehensive plan to raise the government’s coffers, as debt reduction could only come if we can have a surplus budget.

Reference:

A RM1.5 trillion debt hangover, Pankaj C. Kumar, The Star, 28 Jan 2023