The UK has always been a world-leader in university education; home to the famous Oxford, Cambridge, Imperial College and many more. In fact, the U.K. has more top-rated institutions than the rest of the EU put together. It is therefore surprising that higher education has slipped into a financial crisis in the last decade.

The University of Essex has warned staff it is delaying promotions and reviewing future pay awards to cope with a potential £14 million budget shortfall. This is because of a 38 per cent decline in international postgraduate student numbers.

Essex is not alone. The UK’s universities are running out of money. Cuts are being made across the sector as frozen tuition fees, high inflation and falling international student numbers impact finances. According to John Rushforth at the Committee of University Chairs, university bankruptcy is a realistic possibility.

The broader picture is one of a long-term policy failure threatening British

• exports – the UK’s 144 universities contribute £130 billion to the economy, which is more than farming, forestry, fishing, mining, arts and entertainment combined;

• soft power – mandarins and business leaders say British universities are in danger of losing their enviable position in global rankings; and

• university standards – because low student-teacher ratios that traditionally sustained standards are now at risk as universities struggle to stay afloat.

Seventeen of Britain’s universities are in the top 100 of the QS World University Rankings, second only to the US. In 2012, the UK accounted for 15 per cent of the world’s most-cited research papers, down now to 11 per cent.

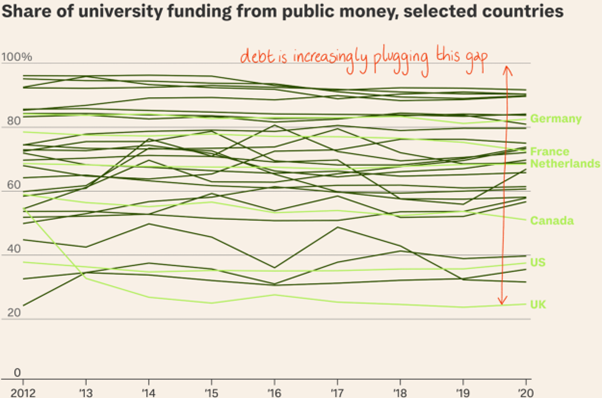

Universities are hemmed in by government policies. Over the last decade, the government has cut funding for teaching by 78 per cent and capped student loans at £9,250, leading to a real-terms decline in domestic fee income of more than a third. In the past three years alone, inflation has eroded universities’ resources by a fifth, with no equivalent of the per-pupil uplift given to schools.

UK research bodies pay 80 per cent of university research budgets. The rest is expected to come from teaching income.

The government’s ambition for the UK to become a science and technology superpower is thus at the mercy of course choices by overseas students who used to account for 20 per cent of the sector’s income.

The government is hoping universities will find productivity gains to cover rising costs. Vice-chancellors see job cuts as the main way to save money. But UK universities punch above their weight thanks mainly to staffing – British universities have on average 13 students per lecturer. In Canada that’s 23:1, and in Australia, 34:1.

Are there any solutions?

The U.K. Government – whether Conservative or Labour – has to recognise the contributions made by the universities. It needs to develop a blueprint to keep funding for leading universities. Use a mixture of the U.S. and European models to finance via:

• Endowment funds (which “power” Harvard and many others);

• Government funds for research and tuition fee (subsidy);

• Student fees and numbers especially the foreign ones. This is not about immigration and visas, it is just education. If you mix the two, then be prepared to shut some of the universities.

“Muddling through” is a British attribute that some say should be taught in business schools. It is “wing it” in America! Whatever, the British institutions need some super-charging to lift them out of the doldrums – will Labour do it?

References:

Broke and shrinking: the downward spiral in British universities, Stephen Armstrong, www.tortoisemedia.com, 25 March 2024

UK universities are on the brink of bankruptcy? Benjamin Edgar, 9 April 2024

No comments:

Post a Comment